The “trust barrier” is the major obstacle hampering the establishment of a large-scale, self-reliance-based resource-pooling fund that can have a transformational impact in addressing urgent problems in our distressed communities. Even black churches are losing trust and credibility among many African Americans. There would be no “trust barrier,” however, if, for instance, five or more of the most respected African Americans got together to start a fund and hired a few highly competent people to run it.

A fund backed by such an ideal “dream team” is unlikely or infeasible (but not impossible!). The more likely way it will happen: a few visionary, motivated, and accomplished entrepreneurs who have solid, unblemished reputations, armed with a sound and credible business plan, convince some less well-known but equally highly-regarded people to back the fund.

Such backing need not even be financial: by virtue of their strong reputations, relationships, and public standing, just lending their credibility, prestige, gravitas, and imprimatur to the fund will provide it with the instant credibility it needs to be able to attract contributions from large numbers of African Americans even at start-up. This is the most likely way a potent large-scale fund will get established.

……

As discussed in the BlackProgress.com article, Financing Black Progress, Part 1: A Publicly Financed “Marshall Plan” Is Unrealistic, So What’s the Alternative? A “Self-Reliance Marshall Plan”?, given the current noxious and racially-charged political environment — in which even the reasonable and very modest American Jobs Act remains stalled in Congress — waiting for massive public investment in initiatives that can transform distressed communities of color is largely futile.

And there is no indication this situation will change in the near future. Regardless of who is president and whether or not Democrats retain control of the Senate and/or retake the House in 2013, Congress will most likely remain closely divided, highly polarized and acrimonious, and is unlikely to pass any legislation to fund, on a substantial enough scale, the types of initiatives that can sufficiently meet the dire needs of these communities.

Rather than simply standing by helplessly and wringing our hands while Congress remains gridlocked and yet another generation of children in distressed communities remains trapped in poverty and dysfunction, we must focus on organizing proactive self-reliance approaches to transform our own communities.

By pooling our resources on a large enough scale, we would be able to amass sufficient capital to adequately attack the most critical problems in our communities, especially with respect to education, entrepreneurship and business development, job creation, and wealth-building. The BlackProgress.com article, Financing Black Progress, Part 2: A Self-Reliance “Marshall Plan”: Creating a National Resource-Pooling Fund, discusses such a resource pooling effort–a National Ventures & Excellence Fund or “EXCEL Fund”.

Such an organization would have the requisite sizable resources, clout, large economies of scale and scope, sharp and concentrated focus, and operational efficiency that will enable it to have much more substantial impact compared to the existing largely small-scale and scattered efforts.

Unfortunately, the “trust barrier,” which evidently has hampered the emergence of such a large-scale effort to date, remains the daunting obstacle to be overcome. James Clingman (of blackonomics.com), an ardent advocate of black “economic empowerment,” laments:

…So why are African Americans so reluctant to pool our money to any great degree outside of the church environment? First of all, many of us simply don’t see our church contributions as a pooling of our resources, despite what it says about the early church in Acts Chapter 2, and we fail to recognize the business aspects of where most of that money goes on Monday morning: Banks, most of which are neither owned by Black folks nor responsive to Blacks when it comes to approving business loans in return for the billions of church dollars held in their vaults.

Second, while we sometimes blindly trust those in charge of the church funds to do the right thing, we do not trust one another enough to pool our resources to develop businesses and such. It seems we are too concerned about who will “be in charge” and who will “handle the money,” and we listen to that negative radio station, WIFM, “What’s in it for me?” [Pooling our Resources]

There is clear evidence that black charitable giving – by the well-off as well as the not-so-well-off – is substantial. Most African Americans want to “give back” and do so in numerous ways, through contributions to churches, charity and community organizations, fraternal organizations, giving circles, etc. According to a recent W. K. Kellogg foundation report, “[n]early two-thirds of African American households donate to organizations and causes, to the tune of $11 billion each year…. Indeed, aggregate charitable giving by African Americans is increasing at a faster rate than either their aggregate income or aggregate wealth.”

Also, a recent Prudential Financial survey report concluded that “[s]olidarity and concern for the financial health and wellbeing of the community is very strong among African American [financial] decision makers…. African Americans are significantly more likely than the general population to cite charitable donations as an important financial goal.” And, in 2003, the Chronicle of Philanthropy reported that blacks donate 25 percent more of their discretionary income to charity compared to whites. (For more, see this previous blog post: Black Philanthropy and the Creation of a Transformational National Resource-Pooling Fund.)

Thus, there is every reason to believe that millions of African Americans would be willing to contribute to a large-scale national resource-pooling fund that credibly demonstrates that their contributions will be put to good use and will have the desired transformational impact.

So how do we break through the “trust barrier”?

To break through the “trust barrier,” the sponsors/managers of the fund must have strong reputations and credibility. Sadly, in light of numerous scandals in recent years, even black churches are losing trust and credibility among many African Americans.

There would be no “trust barrier” if, for example, five to ten of the most respected African Americans in the country (excluding politicians and government officials because their involvement may be inappropriate or prohibited) — say, Colin Powell, Oprah Winfrey, Bill Cosby, Magic Johnson, Richard Parsons, Kenneth Chenault, Condi Rice, Earl Graves, Sr., Ursula Burns, Ben Carson, Henry Louis Gates Jr., Ruth J. Simmons, Bill Russell, T.D. Jakes, Denzel Washington, Morgan Freeman — got together to start a fund and hired a few highly competent people to run it. They would not even need to contribute much money themselves–by virtue of their strong reputations, connections, relationships, and public standing, just lending their credibility, prestige, gravitas, and imprimatur to the fund will provide it with the instant credibility it needs to be able to attract contributions from large numbers of African Americans of all income/wealth levels even at the start.

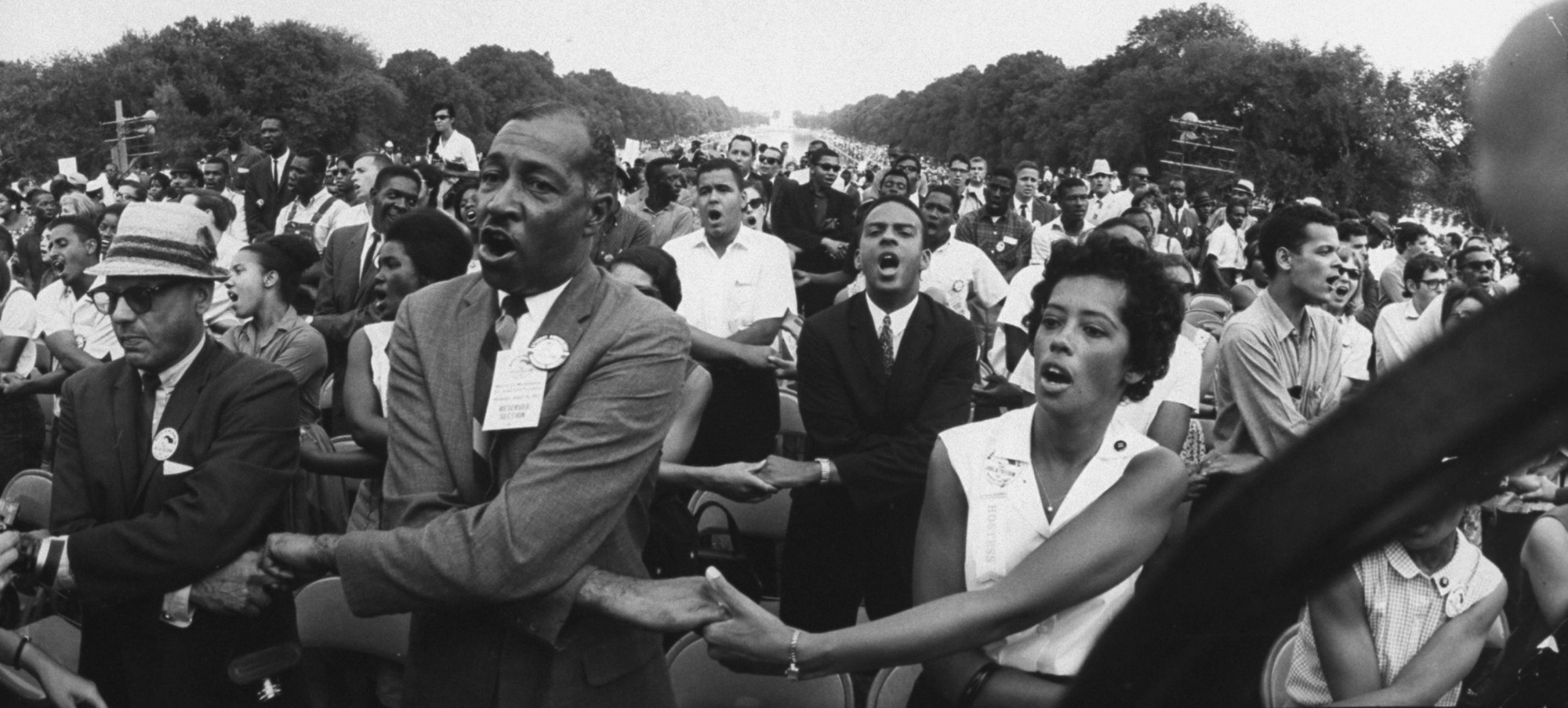

An illustration of the immense collective impact that such a collaboration among highly regarded people can have is illustrated by an event reported in an article by Ponchitta Pierce in the Carnegie Reporter (African American Philanthropy):

One fundraiser [Loida Lewis, widow of the late financier and philanthropist Reginald F. Lewis] attended, a gala to benefit the Studio Museum in Harlem, brought out what Lewis dubs the “crème de la crème” of African American society. Thanks largely (but hardly exclusively) to the patronage of America’s black corporate elite—among them, American Express chairman and chief executive officer Kenneth Chenault; former chairman of the board and chief executive officer of Merrill Lynch, E. Stanley O’Neal; and Richard Parsons, chairman of the board and former CEO of Time-Warner—the benefit raised more than $1.5 million in the course of a single evening. “Wow, it broke a record!” she said, her pride and sense of achievement shining through. “That kind of thing is going to ha ppen more and more,” she told me, noting that the audience was more than 90 percent African American.

A fund backed by such an ideal “dream team,” while most desirable, is unlikely or infeasible (but not impossible!). However, there are, of course, numerous others who are equally reputable and trustworthy but less well-known. In any case, the successful establishment of a fund would most likely require that a few visionary, motivated, and accomplished entrepreneurs who have solid, unblemished reputations, armed with a sound and credible business plan, are able to convince such highly regarded people to back the fund. (See the BlackProgress.com article, Financing Black Progress, Part 2: A Self-Reliance “Marshall Plan”: Creating a National Resource-Pooling Fund, for a discussion of how such “Black Progress Innovators” (BPIs) could make this happen.)

While a huge, national fund with sizable resources and a wide geographical scope is the desired goal, it may be difficult to establish one initially given the usual challenges associated with building large national organizations. Thus, BPIs in different regions of the country, with appropriate backing by highly regarded people in their respective communities, could set up regional resource-pooling funds, e.g., in metropolitan areas such as Washington, DC/Baltimore, Chicago, and Atlanta.

Also, different groups could establish funds based on their priorities and preferred approaches to solving the problems in distressed communities, in accordance with, say, political ideology or faith. For example, a group of BPIs who are centrists (or liberals or faith-driven conservatives) could set up a fund that focuses on specific initiatives that it believes are the best approaches for attacking the problems of distressed communities. It would then be able to attract support from blacks (and non-blacks) who similarly believe in the efficacy of those particular approaches.

Pingback: Stephen DeBerry on the Power of Impact Investing to Foster Black Progress | Black Progress

Pingback: Lisa Hall, President/CEO of Calvert Foundation, on the Potential of Impact Investing to Transform Underserved Communities | Black Progress